# Initialize Otter

import otter

grader = otter.Notebook("lab04.ipynb")

Lab 4: Functions and Visualizations¶

Welcome to Lab 4! This week, we’ll learn about functions, table methods such as apply, and how to generate visualizations!

Recommended Reading:

Lab Submission Deadline: Friday, February 13th at 5pm

Getting help on lab: Whenever you feel stuck or need some further clarification, find a GSI or tutor, and they’ll be happy to help!

As a reminder, here are the policies for getting full credit (Lab is worth 20% of your final grade):

80% of lab credit will be attendance-based. To receive attendance credit for lab, you must attend the full discussion portion (first hour) at which point the GSI will take attendance.

The remaining 20% of credit will be awarded for submitting the programming-based assignment to Pensieve by the deadline (5pm on Friday) with all test cases passing.

Submission: Once you’re finished, run all cells besides the last one, select File > Save Notebook, and then execute the final cell. The result will contain a zip file that you can use to submit on Pensieve.

Let’s begin by setting up the tests and imports by running the cell below.

First, set up the notebook by running the cell below.

import numpy as np

from datascience import *

# These lines set up graphing capabilities.

import matplotlib

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('fivethirtyeight')

import warnings

warnings.simplefilter('ignore', FutureWarning)1. Defining functions¶

Let’s start off by writing a function that converts a proportion to a percentage by multiplying it by 100. For example, the value of to_percentage(.5) should be the number 50 (no percent sign).

A function definition has a few parts.

Name¶

Next comes the name of the function. Like other names we’ve defined, it can’t start with a number or contain spaces. Let’s call our function to_percentage:

def to_percentageSignature¶

Next comes the signature of the function. This tells Python the number of arguments in the function and the names of those arguments. An argument is a value that is passed into the function when it is used/called. A function can have any number of arguments (including 0!).

to_percentage should take one argument, and we’ll call that argument proportion since it should be a proportion.

def to_percentage(proportion)If we want our function to take more than one argument, we add a comma between each argument name i.e to_percentage(proportion, decimals). Note that if we had zero arguments, we’d still place the parentheses () after that name.

We put a colon after the signature to tell Python that the next indented lines are the body of the function. Make sure you remember the colon!

def to_percentage(proportion):Documentation¶

Functions can do complicated things, so you should write an explanation of what your function does. For small functions, this is less important, but it’s a good habit to learn from the start (although documentation isn’t strictly required). Conventionally, Python functions are documented by writing an indented triple-quoted string:

def to_percentage(proportion):"""Converts a proportion to a percentage."""Body¶

Now we start writing code that runs when the function is called. This is called the body of the function and every line must be indented with a tab. Any lines that are not indented and left-aligned with the def statement are considered outside the function.

Some notes about the body of the function:

We can write code that we would write anywhere else.

We use the arguments defined in the function signature. We can do this because values are assigned to those arguments when we call the function.

We generally avoid referencing variables defined outside the function. If you would like to reference variables outside of the function, pass them through as arguments!

Now, let’s give a name to the number we multiply a proportion by to get a percentage:

def to_percentage(proportion):"""Converts a proportion to a percentage."""

factor = 100return¶

The special instruction return is part of the function’s body and tells Python to make the value of the function call equal to whatever comes right after return. We want the value of to_percentage(.5) to be the proportion .5 times the factor 100, so we write:

def to_percentage(proportion):"""Converts a proportion to a percentage."""

factor = 100

return proportion * factorreturn only makes sense in the context of a function, and can never be used outside of a function. return is always the last line of the function because Python stops executing the body of a function once it hits a return statement. Make sure to include a return statement unless you don’t expect the function to return anything.

Note: return inside a function tells Python what value the function evaluates to. However, there are other functions, like print, that have no return value. For example, print simply prints a certain value out to the console.

In short, return is used when you want to tell the computer what the value of some variable is, while print is used to tell you, a human, its value.

Question 1.1. Define to_percentage in the cell below. Call your function to convert the proportion .2 to a percentage. Name that percentage twenty_percent.

def ...

''' (Replace this with your documentation) '''

... = ...

return ...

twenty_percent = ...

twenty_percentgrader.check("q11")Here’s something important about functions: the names assigned within a function body are only accessible within the function body. Once the function has returned, those names are gone. So even if you created a variable called factor and defined factor = 100 inside of the body of the to_percentage function and then called to_percentage, factor would not have a value assigned to it outside of the body of to_percentage:

Note: Below, you should see a NameError error message indicating that the name 'factor' is not defined. Python throws this error because factor has not been defined outside of the body of the to_percentage function.

# You should get an error when you run this. (If you don't,

# you might have defined factor somewhere above.)

factorLike you’ve done with built-in functions in previous labs (max, abs, etc.), you can pass in named values as arguments to your function.

Question 1.2. Use to_percentage again to convert the proportion named a_proportion (defined below) to a percentage called a_percentage.

Note: You don’t need to define to_percentage again! Like other named values, functions stick around after you define them.

a_proportion = 2**(0.5) / 2

a_percentage = ...

a_percentagegrader.check("q12")In the following cell, we will define a function called disemvowel. It takes in a single string as its argument. It returns a copy of that string, but with all the characters that are vowels removed. (In English, the vowels are the characters “a”, “e”, “i”, “o”, and “u”.)

To remove all the "a"s from a string, we used a_string.replace("a", ""). The .replace method for strings returns a new string, so we can call replace multiple times, one after the other.

def disemvowel(a_string):

"""Removes all vowels from a string."""

return a_string.replace("a", "").replace("e", "").replace("i", "").replace("o", "").replace("u", "")

# An example call to the function. (It's often helpful to run

# an example call from time to time while we're writing a function,

# to see how it currently works.)

disemvowel("Can you read this without vowels?")Calls on calls on calls¶

Just as you write a series of lines to build up a complex computation, it’s useful to define a series of small functions that build on each other. Since you can write any code inside a function’s body, you can call other functions you’ve written.

If a function is like a recipe, defining a function in terms of other functions is like having a recipe for cake telling you to follow another recipe to make the frosting, and another to make the jam filling. This makes the cake recipe shorter and clearer, and it avoids having a bunch of duplicated frosting recipes. It’s a foundation of productive programming.

For example, suppose you want to count the number of characters that aren’t vowels in a piece of text. One way to do this is to remove all the vowels and count the size of the remaining string.

Question 1.3. Write a function called num_non_vowels. It should take a string as its argument and return a number. That number should be the number of characters in the argument string that aren’t vowels. You should use the disemvowel function we provided above inside of the num_non_vowels function.

Hint: The function len takes a string as its argument and returns the number of characters in it.

def num_non_vowels(a_string):

"""The number of characters in a string, minus the vowels."""

...

# Try calling your function yourself to make sure the output is what

# you expect. grader.check("q13")Functions can also encapsulate code that displays output instead of computing a value. For example, if you call print inside a function, and then call that function, something will get printed.

The movies_by_year dataset in the textbook has information about movie sales in recent years. Suppose you’d like to display the year with the 5th-highest total gross movie sales, printed within a sentence. You might do this:

movies_by_year = Table.read_table("movies_by_year.csv")

rank = 5

fifth_from_top_movie_year = movies_by_year.sort("Total Gross", descending=True).column("Year").item(rank-1)

print("Year number", rank, "for total gross movie sales was:", fifth_from_top_movie_year)After writing this, you realize you also wanted to print out the 2nd and 3rd-highest years. Instead of copying your code, you decide to put it in a function. Since the rank varies, you make that an argument to your function.

Question 1.4. Write a function called print_kth_top_movie_year. It should take a single argument - the rank of the year (like 2, 3, or 5 in the above examples) as an integer - and should use the table movies_by_year. It should print out a message like the one above.

Note: Your function shouldn’t have a return statement.

def print_kth_top_movie_year(k):

...

print(...)

# Example calls to your function:

print_kth_top_movie_year(2)

print_kth_top_movie_year(3)grader.check("q14")print is not the same as return¶

The print_kth_top_movie_year(k) function prints the total gross movie sales for the year that was provided! However, since we did not return any value in this function, we can not use it after we call it. Let’s look at an example of another function that prints a value but does not return it.

def print_number_five():

print(5)print_number_five()However, if we try to use the output of print_number_five(), we see that the value 5 is printed but we get a TypeError when we try to add the number 2 to it!

print_number_five_output = print_number_five()

print_number_five_output + 2It may seem that print_number_five() is returning a value, 5. In reality, it just displays the number 5 to you without giving you the actual value! If your function prints out a value without returning it and you try to use that value, you will run into errors, so be careful!

Think about how you might add a line of code to the print_number_five function (after print(5)) so that the code print_number_five_output + 5 would result in the value 10, rather than an error.

2. Functions and CEO Incomes¶

In this question, we’ll look at the 2015 compensation of CEOs at the 100 largest companies in California. The data was compiled from a Los Angeles Times analysis, and ultimately came from filings mandated by the SEC from all publicly-traded companies. Two companies have two CEOs, so there are 101 CEOs in the dataset.

We’ve copied the raw data from the LA Times page into a file called raw_compensation.csv. (The page notes that all dollar amounts are in millions of dollars.)

raw_compensation = Table.read_table('raw_compensation.csv')

raw_compensationWe want to compute the average of the CEOs’ pay. Try running the cell below.

np.average(raw_compensation.column("Total Pay"))You should see a TypeError. Let’s examine why this error occurred by looking at the values in the Total Pay column. To do so, we can use the type function. This function tells us the data type of the object that we pass into it. Run the following cells to see what happens when we pass in 23, 3.5, and "Hello" to the type function. Do their outputs make sense?

type(23)type(3.5)type("Hello")Question 2.1. Use the type function and set total_pay_type to the type of the first value in the “Total Pay” column.

total_pay_type = ...

total_pay_typegrader.check("q21")Question 2.2. You should have found that the values in the Total Pay column are strings. It doesn’t make sense to take the average of string values, so we need to convert them to numbers. Extract the first value in Total Pay. It’s Mark Hurd’s pay in 2015, in millions of dollars. Call it mark_hurd_pay_string.

mark_hurd_pay_string = ...

mark_hurd_pay_stringgrader.check("q22")Question 2.3. Convert mark_hurd_pay_string to a number of dollars.

Some hints, as this question requires multiple steps:

The string method

stripwill be useful for removing the dollar sign; it removes a specified character from the start or end of a string. For example, the value of"100%".strip("%")is the string"100".You’ll also need the function

float, which converts a string that looks like a number to an actual number. Don’t worry about the whitespace at the end of the string; thefloatfunction will ignore this.

Finally, remember that the answer should be in dollars, not millions of dollars. For example:

If the table says a CEO was paid

$9, we know this is in millions of dollars.Converting this to

$9000000changes it to be in dollars.

mark_hurd_pay = ...

mark_hurd_paygrader.check("q23")To compute the average pay, we need to do this for every CEO. But that looks like it would involve copying this code 101 times.

We’ll instead use functions to perform this computation. Later in this lab, we’ll see the payoff: we can call that function on every pay string in the dataset at once.

Question 2.4. Copy the expression you used to compute mark_hurd_pay, and use it as the return expression of the function below. But make sure you replace the specific mark_hurd_pay_string with the generic pay_string name specified in the first line in the def statement.

Hint: When dealing with functions, you should generally not be referencing any variable outside of the function. Usually, you want to be working with the arguments that are passed into it, such as pay_string for this function. If you’re using mark_hurd_pay_string within your function, you’re referencing an outside variable!

def convert_pay_string_to_number(pay_string):

"""Converts a pay string like '$100' (in millions) to a number of dollars."""

...grader.check("q24")Running that cell doesn’t convert any particular pay string. Instead, it creates a function called convert_pay_string_to_number that can convert any string with the right format to a number representing millions of dollars.

We can call our function just like we call the built-in functions we’ve seen. It takes one argument, a string, and it returns a float.

convert_pay_string_to_number('$42')convert_pay_string_to_number(mark_hurd_pay_string)# We can also compute Safra Catz's pay in the same way:

convert_pay_string_to_number(raw_compensation.where("Name", are.containing("Safra")).column("Total Pay").item(0))With this function, we don’t have to copy the code that converts a pay string to a number each time we wanted to convert a pay string. Now we just call a function whose name says exactly what it’s doing.

3. applying functions¶

Defining a function is a lot like giving a name to a value with =. In fact, a function is a value just like the number 1 or the text “data”!

For example, we can make a new name for the built-in function max if we want:

our_name_for_max = max

our_name_for_max(2, 6)The old name for max is still around:

max(2, 6)Try just writing max or our_name_for_max (or the name of any other function) in a cell, and run that cell. Python will print out a (very brief) description of the function.

maxNow try writing max? or our_name_for_max? (or the name of any other function) in a cell, and run that cell. A information box should show up at the bottom of your screen a longer description of the function

Note: You can also press Shift+Tab after clicking on a name to see similar information!

our_name_for_max?Let’s look at what happens when we set maxto a non-function value. Python now thinks you’re trying to use a number like a function, which causes an error. Look out for any functions that might have been renamed when you encounter this type of error.

max = 6

max(2, 6)# This cell resets max to the built-in function. Just run this cell, don't change its contents

import builtins

max = builtins.maxWhy is this useful? Since functions are just values, it’s possible to pass them as arguments to other functions. Here’s a simple but not-so-practical example: we can make an array of functions.

make_array(max, np.average, are.equal_to)Question 3.1. Make an array containing any 3 other functions you’ve seen. Call it some_functions.

some_functions = ...

some_functionsgrader.check("q31")Working with functions as values can lead to some funny-looking code. For example, see if you can figure out why the following code works.

make_array(max, np.average, are.equal_to).item(0)(4, -2, 7)A more useful example of passing functions to other functions as arguments is the table method apply.

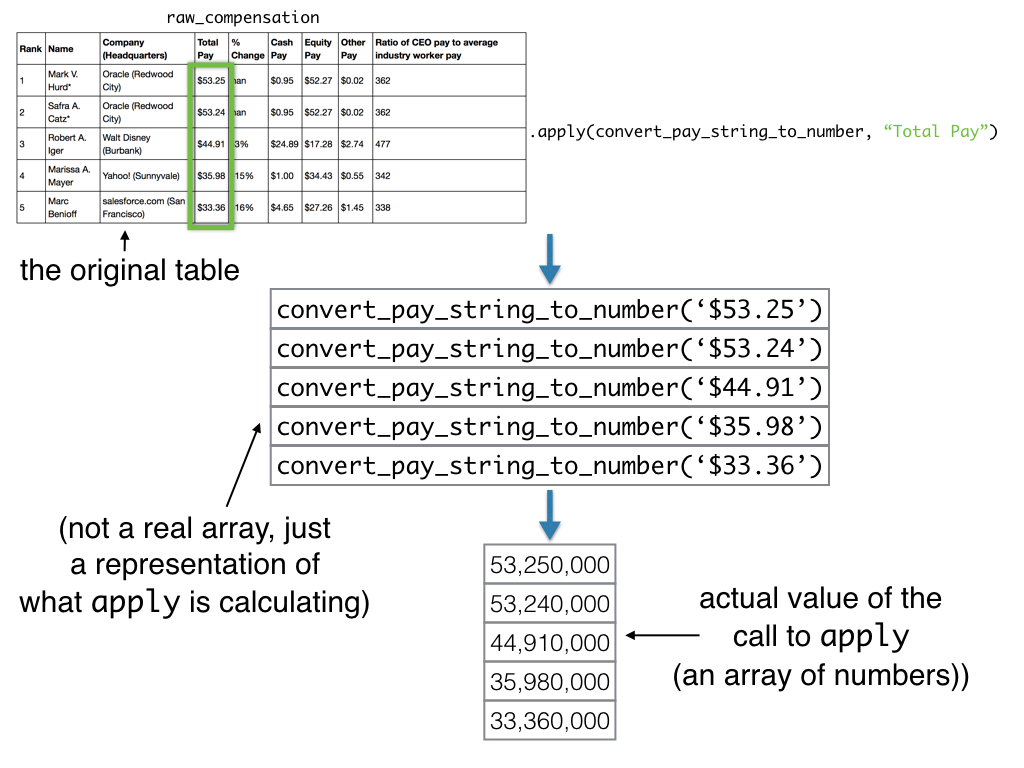

apply calls a function many times, once on each element in a column of a table. It produces an array of the results. Here we use apply to convert every CEO’s pay to a number, using the function you defined:

Note: You’ll see an array of numbers like 5.325e+07. This is Python’s way of representing scientific notation. We interpret 5.325e+07 as 5.325 * 10**7, or 53,250,000.

raw_compensation.apply(convert_pay_string_to_number, "Total Pay")Here’s an illustration of what that did:

Note that we didn’t write raw_compensation.apply(convert_pay_string_to_number(), “Total Pay”) or raw_compensation.apply(convert_pay_string_to_number(“Total Pay”)). We just passed the name of the function, with no parentheses, to apply, because all we want to do is let apply know the name of the function we’d like to use and the name of the column we’d like to use it on. apply will then call the function convert_pay_string_to_number on each value in the column for us! Also note that calling tbl.apply does not alter the original table in any way.

Question 3.2. Using apply, make a table that’s a copy of raw_compensation with one additional column called Total Pay ($). That column should contain the result of applying convert_pay_string_to_number to the Total Pay column (as we did above). Call the new table compensation.

compensation = raw_compensation.with_column(

"Total Pay ($)",

...

)

compensationgrader.check("q32")Now that we have all the pays as numbers, we can learn more about them through computation.

Question 3.3. Compute the average total pay of the CEOs in the dataset.

average_total_pay = ...

average_total_paygrader.check("q33")Question 3.4 Companies pay executives in a variety of ways: in cash, by granting stock or other equity in the company, or with ancillary benefits (like private jets). Compute the proportion of each CEO’s pay that was cash. (Your answer should be an array of numbers, one for each CEO in the dataset.)

Hint: What function have you defined that can convert a string to a number?

cash_proportion = ...

cash_proportiongrader.check("q34")Why is apply useful?

For operations like arithmetic, or the functions in the NumPy library, you don’t need to use apply, because they automatically work on each element of an array. But there are many things that don’t. The string manipulation we did in today’s lab is one example. Since you can write any code you want in a function, apply gives you greater control over how you operate on data.

Check out the % Change column in compensation. It shows the percentage increase in the CEO’s pay from the previous year. For CEOs with no previous year on record, it instead says “(No previous year)”. The values in this column are strings, not numbers, so like the Total Pay column, it’s not usable without a bit of extra work.

Given your current pay and the percentage increase from the previous year, you can compute your previous year’s pay. For example, if your pay is this year, and that’s an increase of 50% from the previous year, then your previous year’s pay was , or $80.

Question 3.5 Create a new table called with_previous_compensation. It should be a copy of compensation, but with the “(No previous year)” CEOs filtered out, and with an extra column called 2014 Total Pay ($). That column should have each CEO’s pay in 2014.

Hint 1: You can print out your results after each step to make sure you’re on the right track.

Hint 2: We’ve provided a structure that you can use to get to the answer. However, if it’s confusing, feel free to delete the current structure and approach the problem your own way!

# Definition to turn percent to number

def percent_string_to_num(percent_string):

"""Converts a percentage string to a number."""

return ...

# Compensation table where there is a previous year

having_previous_year = ...

# Get the percent changes as numbers instead of strings

# We're still working off the table having_previous_year

percent_changes = ...

# Calculate the previous year's pay

# We're still working off the table having_previous_year

previous_pay = ...

# Put the previous pay column into the having_previous_year table

with_previous_compensation = ...

with_previous_compensationgrader.check("q35")Question 3.6 Determine the average pay in 2014 of the CEOs that appear in the with_previous_compensation table. Assign this value to the variable average_pay_2014.

average_pay_2014 = ...

average_pay_2014grader.check("q36")4. Histograms¶

Earlier, we computed the average pay among the 101 CEOs in our dataset. The average doesn’t tell us everything about the amounts CEOs are paid, though. Maybe just a few CEOs make the bulk of the money, even among these 101.

We can use a histogram method to display the distribution of a set of numbers. The table method hist takes a single argument, the name of a column of numbers. It produces a histogram of the numbers in that column.

Question 4.1. Make a histogram of the total pay of the CEOs in compensation. Check with a peer or instructor to make sure you have the right plot. If you get a warning, ignore it.

Hint: If you aren’t sure how to create a histogram, refer to the Python Reference sheet.

...Question 4.2. How many CEOs made more than $30 million in total pay? Find the value using code, then check that the value you found is consistent with what you see in the histogram.

num_ceos_more_than_30_million_2 = ...

num_ceos_more_than_30_million_2grader.check("q42")5. Project 1 Partner Form¶

Project 1 will be released on Friday, 2/13 at 5PM!

You have the option of working with a partner that is enrolled in your lab. Your GSI should have sent out a form to match you up with a partner for this project. Set submitted to True to confirm that you’ve submitted the form.

If you are in Self-Service lab, you may assign submitted to True without submitting anything.

submitted = ...grader.check("q5")Pets of Data 8¶

Phoenix, Obi, Bean, and Pricess are so proud of you for finishing the assignment.

Congrats on completing Lab 4!

You’re done with lab!

Important submission information:

Run all the tests and verify that they all pass

Save from the File menu

Run the final cell to generate the zip file

Click the link to download the zip file

Then, go to Pensieve and submit the zip file to the corresponding assignment. The name of this assignment is “Lab XX Autograder”, where XX is the lab number -- 01, 02, 03, etc.

If you finish early in Regular Lab, ask one of the staff members to check you off.

It is your responsibility to make sure your work is saved before running the last cell.

To double-check your work, the cell below will rerun all of the autograder tests.

grader.check_all()Submission¶

Make sure you have run all cells in your notebook in order before running the cell below, so that all images/graphs appear in the output. The cell below will generate a zip file for you to submit. Please save before exporting!

# Save your notebook first, then run this cell to export your submission.

grader.export(pdf=False)